Community Networks: Critical Infrastructure For Rural Connectivity In India

As India goes digital-first, millions remain offline. Locally run networks show how connectivity can be built where markets fall short.

In India, access to reliable digital connectivity increasingly determines who can learn, work, access public services, and participate fully in society. Yet for millions of people in rural and remote regions, fast and dependable internet access remains out of reach. As the country accelerates its push toward digital-first governance and services, this gap is no longer just a question of access: it is a question of infrastructure. Community networks offer a practical, people-centered model for closing that gap and should be recognized as critical digital infrastructure.

Digital Connectivity as Critical Infrastructure

Today, ‘digital infrastructure’ has emerged as a significant infrastructure necessity, comparable to traditional necessities such as power, water, and roads. Post-COVID, digital infrastructure emerged as a core utility for citizens living in emerging economies to access a variety of services, from online banking to accessing educational content.

Yet, being online is still an urban privilege. 1 in 6 rural homes (16.7%) are unconnected. Twice that of the urban households, where only 1 in 12 (8.4%) remain offline. Where connections exist for rural communities, they are slower. Only 3.8 per cent of rural households have access to fibre connections compared to 15.3 per cent of urban households – marking urban households four times more likely to access fibre-based broadband. A similar gap exists for fixed broadband shared over Wi-Fi: 24 per cent of urban households have access, compared to just 9.1 per cent of rural households. As a result, mobile internet access has become the near-universal form of connectivity for rural regions. The critical infrastructure for fast and reliable broadband remains concentrated in urban areas, further perpetuating the digital divide and impacting rural users’ ability to access internet services and fully benefit from them.

Why Traditional Connectivity Models Fall Short

Traditionally, network infrastructure has been built by government and private stakeholders through centralized top-down models such as installing mobile and network towers or laying fiber. While effective in many urban contexts, these approaches often fail to account for the realities of rural and remote communities where connectivity needs, geography, and capacity differ significantly.

As a result, networks are frequently misaligned with local priorities and largely unaccountable to community governance and knowledge. True development requires more than physical infrastructure alone: it demands connectivity that is affordable, reliable, and embedded in local communities, building trust, skills, and the ability to use digital services meaningfully. In this context, community-led and-owned network infrastructure fulfills the requirements of rural communities where network infrastructure is not merely providing internet access, but also developing the trust and skills to access internet services effectively.

Community Networks as an Infrastructural Alternative

Addressing gaps in connectivity infrastructure left by the state and private bodies, community-owned and operated networks, also known as community networks (CNs), play an important role in providing last-mile connectivity. Framed as an infrastructural solution, these community networks are focused on the specific needs of the community and enable decentralized, decolonialized approaches to technology that don’t follow such hierarchical systems, infrastructure, and governance models. Community networks are also referred to as ‘Communal Infrastructure’ that are designed on based on four principles:

- People-centered: establishing and embracing human connections.

- Inclusive design: different network designs matter for different communities.

- Co-responsibility: every stakeholder in the community takes responsibility for the network.

- Community ownership: local ownership to establish, operate and manage the network democratically and focus on people-centered rights and privacy.

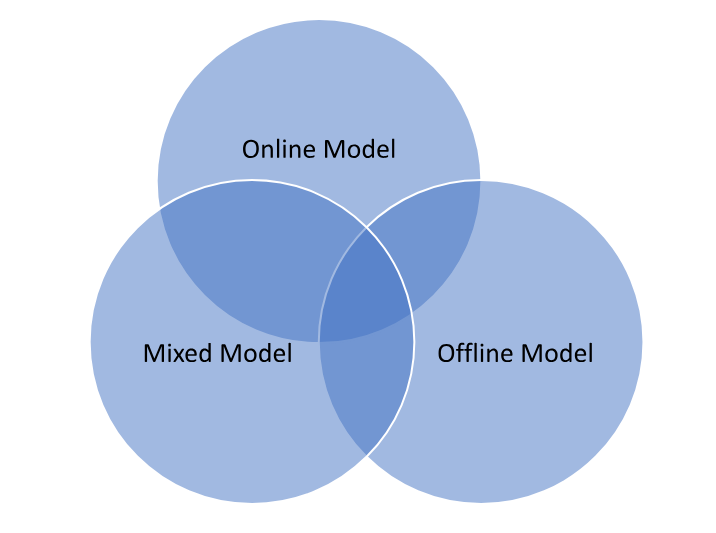

Community-owned infrastructure is designed through a set of agreements and relationships that support the provision of hardware, software, required applications, and local space needed to provide internet-based services that are requested by the community. Based on local needs and use cases, CNs adapt the design of their network infrastructure accordingly. Three types of community networks that are operating across the globe, including India (Figure 3)

- Online model: Uses backhaul from the traditional ISPs to distribute internet services to the community.

- Offline model: Created local network infrastructure and applications that operate on the local network to connect two or more communities.

- Mixed model:Combines internet access and local networks, using each interchangeably based on community needs and the availability of existing resources.

Community Networks in Practice: Examples from India

Community networks in India have adopted different approaches while providing internet-based services. Technologists, academic researchers, civil society organizations and social enterprises in India have deployed community-owned wireless networks and experimented with different technologies and models, giving alternatives to the existing internet regimes.

One example is the ‘HEALTH’ community network, deployed by a team from the National Institute of Technology Karnataka (NITK), Surathkal in Agumbe village in Karnataka’s rainforest region. The project draws fibre cables from existing electrical poles and connects them to WiFi access points in individual houses or public spaces. HEALTH, short for healthcare, education, agriculture, livelihood, technology and heritage, adapts fibre-to-home technology to local conditions and needs.

Today, the HEALTH community network connects the Gram Panchayat office, conservation research institutions, police stations, local schools, homestays, and other public spaces. More than 100 internet access points have been deployed across Agumbe, demonstrating how locally adapted infrastructure can support diverse community institutions.

A similar need-driven approach can be seen in the remote villages of Dhadgaon block in Nandurbar district, Maharashtra, where residents often struggle to receive one-time passwords (OTPs) on their mobile phones, which is necessary for e-KYC (know your customer) verification. In some cases, locals must walk hours through difficult terrain simply to access a mobile network. In response, Nitesh Bhardwaj established the Aadiwasi Janjagruti community network, that brings hyper-local content that empowers tribal communities to access their rights, opportunities, and entitlements while promoting sustainable development.

Women-centered community networks have also emerged as powerful connectivity models. eDost, a women-centric community network under BAIF’s Pathardi Community-Centered Connectivity initiative, operates across seven villages of Palghar district, located in Maharashtra state and is supported through APC's Community Network Learning (Pathfinder) grant. Women are trained to use digital tools and manage services, enabling the network to support livelihoods as well as access to government and financial services.

Using connectivity provided through wireless networks or open BTS deployments in shared public spaces, eDoST provides financial services such as cash withdrawals, balance enquiries, and e-governance services. By centering women as operators and intermediaries, the network embeds digital skills and trust directly within the community.

Community networks have also been deployed to support resilience in disaster-prone regions. IEEE Philanthropy India has connected 205 disaster-prone villages across rural Karnataka and Kerala by using local schools as access points for neighboring communities. It is estimated that over 1,500 people have directly benefited, and the project has emphasized sustainability by training over 500 young students as wireless network technicians. IEEE Philanthropy is planning to continue this community network model and expand to other rural schools in the country.

In contexts where bringing internet backhaul is costly or impractical, hybrid community network models have proven particularly effective. Community Reach (CR) Bolo, an initiative of Jadeite Solutions with support from the IEEE SA, established a community network utilizing the existing infrastructure of the community radio station – Radio Bulbul in Bhadrak district of Odisha.

The project repurposed the radio tower, local server space, computers, and bandwidth to create a wireless point-to-point network connecting schools and self-help group centers within a seven-kilometer radius. Recognizing that many community members are more comfortable with voice-based services, CR Bolo integrated an Interactive Voice Response (IVR) system that operates both on the Global System for Mobile Communications (GSM) network and the local network. This enabled Radio Bulbul not only to distribute information and services, but also to collect feedback and strengthen community participation.

It is imperative to say that community network operators do not adopt a singular model; they are defined based on the needs of the community. The supply-chain model of these networks is quite simple, with connectivity provided based on local requirements. The social and economic architecture of community networks is, by design, multi-stakeholder, since their operations are managed by a variety of stakeholders, from local authorities to school-teachers, enterprises, radio stations, women-centric groups, and communities living in the region.

Their community-driven design, adaptability and multi-stakeholder governance make them unique and well-suited for bringing connectivity where traditional systems are failing to deliver internet services. As the country increasingly relies on digital access–based services across sectors, recognizing, and supporting community networks as a critical infrastructure is both a practical and moral imperative. By institutionalizing CNs within national and state-level policies and making it a universal requirement, India can build a more inclusive, resilient, and people-centered digital future.

Ritu Srivastava is an experienced professional and entrepreneur exploring the concepts of meaningful connectivity, its sustainability, and impact studies that highlight the social, economic, and gender aspects of connectivity.

She has over 16 years’ experience in areas of community network, research, and policy advocacy documents around rural connectivity solutions. She has closely worked with community networks to understand the challenges, and engagement of communities, and design specific learning methods/frameworks for barefoot women wireless engineers to sustain these models and further take to policy-level discourse.

She has represented India at the Global Network Initiative, the UN Human Rights Council and the High-Level Panel for Digital Cooperation. Currently, she is a Program Manager for FN Entrepreneurs Mentorship (FNEM) and Connecting the Unconnected (CTU) Challenge at IEEE and Director of Jadeite Solutions. She holds a Master's degree in Telecommunication and MBA in IT. She also holds a degree in UN Human Rights Mechanism and International Policy.

Getting Bots to Respect Boundaries

I’ve recently completed my case study for my Internet Society fellowship: Getting Bots to Respect Boundaries: How AI Crawlers Are Straining Web Infrastructure.

Drawing on examples from Wikimedia, Project Gutenberg, APC, and more, I catalogue the defensive measures publishers are now using, alongside newer approaches currently in development. None are perfect: some no longer work or are likely to fail soon, and many undermine openness and block legitimate users. I close by outlining a few ways this could get better, including how shifting incentives, better crawler behaviour, and clearer preference signalling might help.

I plan to finalize it in the next week, and share it in the next edition of IX. I'd also like to share it with the IETF AI Preferences Working Group. Before I do that, I’d really value feedback from the IX community: is anything missing or underdeveloped? Do you have ideas on how to shift incentives or practices to make AI crawling less damaging for publishers? Please share them with me! editor@exchangepoint.tech.

Support the Internet Exchange

If you find our emails useful, consider becoming a paid subscriber! You'll get access to our members-only Signal community where we share ideas, discuss upcoming topics, and exchange links. Paid subscribers can also leave comments on posts and enjoy a warm, fuzzy feeling.

Not ready for a long-term commitment? You can always leave us a tip.

This Week's Links

Internet Governance

- Civil society groups warn that the draft rules for implementing the UN Cybercrime Convention could enable politicized exclusion and limit transparency unless stronger safeguards for participation, openness, and human rights are put in place from the outset. https://www.gp-digital.org/news/joint-civil-society-statement-on-the-draft-rules-of-procedure-of-the-conference-of-states-parties-to-the-un-cybercrime-convention

- The European Commission has formally designated WhatsApp as a Very Large Online Platform (VLOP) under the Digital Services Act (DSA). (PS, is VLOP an acronym or an initialism?) https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/news/commission-designates-whatsapp-very-large-online-platform-under-digital-services-act

- The EU’s proposed Digital Networks Act could reopen the door to “Fair Share” fees that would require large online companies like streaming services, social media platforms, or cloud providers to pay internet network operators for the traffic they generate warns Carl Gahnberg, director of Policy Development and Research at Internet Society. https://www.internetsociety.org/blog/2026/01/fair-share-and-the-digital-networks-act-dna-three-concerns

- The AI Standards Exchange Database is a one stop gateway to AI standards, reports and news from global standards development organizations. https://aiforgood.itu.int/ai-standards-exchange

Digital Rights

- We are in a phone war, writes Julia Angwin in the New York Times. Your phone is one of the last tools standing between state violence and accountability. As federal agents increasingly treat being filmed as a threat, the simple act of recording has become a frontline act of resistance. https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/26/opinion/minnesota-minneapolis-phone-ice-shooting.html

- Iran’s January internet shutdown is not just a domestic crackdown but a warning sign that governments around the world are increasingly turning to digital blackouts, surveillance, and AI-powered control to suppress dissent and hold on to power. https://thebulletin-org.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/thebulletin.org/2026/01/irans-internet-shutdown-tells-a-larger-story-digital-repression-is-on-the-rise/amp

- Related: As Iran’s latest internet shutdown cuts millions off from the world and shields mass repression from view, civil society groups including WITNESS, Access Now, ARTICLE 19, and Centre for Human Rights in Iran are urging governments and tech companies to fast-track direct-to-cell satellite connectivity as a humanitarian lifeline for people living under blackout. https://www.witness.org/civil-society-coalition-launches-campaign-calling-for-direct-to-cell-satellite-connectivity-amid-irans-internet-shutdowns

- A report by The Citizen Lab shows that Jordanian authorities used technology made by the Israeli company Cellebrite to extract data from the phones of Gaza war protestors. https://www.occrp.org/en/news/jordan-used-israeli-tech-to-crack-phones-of-gaza-war-protestors-report

- We have a right not to be generated, writes Odanga Madung, Technology and Human Rights fellow at the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy. “We can build systems that respect bodily autonomy in digital space the same way we've learned to respect it in physical space.” https://www.hks.harvard.edu/centers/carr-ryan/our-work/carr-ryan-commentary/we-have-right-not-be-generated

Technology for Society

- Upscrolled, a social media platform supported by the Tech for Palestine incubator, sees a surge in downloads following TikTok’s US takeover. https://techcrunch.com/2026/01/26/social-network-upscrolled-sees-surge-in-downloads-following-tiktoks-us-takeover

Privacy and Security

- Whatsapp launches a new lockdown-style feature called Strict Account Settings that will lock to the most restrictive settings, and it will limit how your WhatsApp works in some ways, like blocking attachments and media from people not in your contacts. https://blog.whatsapp.com/whatsapps-latest-privacy-protection-strict-account-settings

- The FBI has joined the chat. After right-wing media figures claimed they joined Minnesota Signal chats that tracked ICE agents and accused participants of obstructing law enforcement, FBI Director Kash Patel said the bureau had opened a criminal investigation into those encrypted group chats. Free speech advocates say the First Amendment generally protects people who share legally obtained information unless there’s evidence of illegal conduct. https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/internet/fbi-investigating-minnesota-signal-minneapolis-group-ice-patel-kash-rcna256041

- A class-action lawsuit claims that WhatsApp can access users’ private messages despite its end-to-end encryption, but security experts say the case offers little technical evidence and appears weak. WhatsApp says the suit is frivolous and possibly linked to unrelated litigation involving spyware maker NSO Group.https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2026/01/29/whatsapp-lawsuit-read-messages-denied

- World's First Pure Post-Quantum DNS-over-QUIC Service is LIVE! Says Santosh Pandit. The "Harvest Now, Decrypt Later" threat is real, he says, and Quantum computers are advancing faster than expected. DNS privacy needs quantum-resistant protection TODAY. Try it out: https://practicallyunhackable.com/doq

Upcoming Events

- The Extraction Economy with Tim Wu and Julia Angwin. Feb 3. New York, NY. https://events.columbia.edu/cal/event/eventView.do?b=de&calPath=/public/cals/MainCal&guid=CAL-00bbdb71-9b0cabe2-019b-0e5c0971-00002f10events@columbia.edu&recurrenceId=

- [Open Data Day] Internet Infrastructure of London Walking Tour. London, UK. March 8. https://luma.com/zy0hjdkx

- ATmosphereConf Vancouver. Early Bird tickets are now on sale on a sliding scale. Vancouver, Canada. March 26-29. https://news.atmosphereconf.org/3m76dixo4is2w?auth_completed=true

- Magnanrama. Portraits, Networks, and News of Nathalie Magnan, a group exhibition dedicated to Nathalie Magnan, media theorist, filmmaker, cyberfeminist and hacktivist, sailor of seas and internets, who passed away in 2016. Nice, France. Feb 20-May 31. https://villa-arson.fr/en/programmation/agenda/vernissage-des-expositions-hito-steyerl-magnanrama

- The Global Gathering (GG) brings together groups from around the world that are working on the most urgent technology-related challenges affecting human rights, social justice, civil society, and journalism at the local, regional and global levels. Applications are open now! September 4-6. Estoril, Portugal. https://gathering.digitalrights.community

Careers and Funding Opportunities

- John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation: Director, AI Opportunity. Chicago, IL. https://macfound.wd1.myworkdayjobs.com/en-US/MAC_FOUND_EXT_CAREERS/details/Director--AI-Opportunity_REQ-000315

- The Surveillance Technology Oversight Project (S.T.O.P.): Legal Director. New York, NY. https://www.stopspying.org/staff-openings

- HURIDOCS (Human Rights Information and Documentation Systems): Global Repository Project Coordinator. Global Remote. https://www.idealist.org/en/nonprofit-job/8339f49660b34392bba351e57c1d1a6a-global-repository-project-coordinator-10-month-consultancy-with-a-possibility-of-extension-huridocs-human-rights-information-and-documentation-systems-geneva

What did we miss? Please send us a reply or write to editor@exchangepoint.tech.

Comments ()