Public interest technologists; Internet complexity

The Public Interest Technology Group (PITG) is a dynamic collective of individuals united by a common cause: advocating for the public interest in global standards setting. Our group is diverse, consisting of members from academia, the corporate world, and civil society organizations, all focused on the nexus of human rights and equity, and internet infrastructure.

Since the 2016 IETF 96 meeting in Berlin we have met monthly online and in person at each IETF meeting, creating a platform for ongoing dialogues and collaborations among public interest technologists, funding bodies, and key players in Internet governance and standardization. I was privileged to chair the group from 2018-22.

The growth of our group over the years has been a testament to the increasing recognition of the need for public interest advocacy in technical domains. Our influence has extended beyond the IETF, encompassing other major standardization bodies like the W3C, IEEE and ITU. Our discussions have also broadened to address emerging issues of technology governance across various layers of the internet. The PITG incubated the I-Star newsletter, the precursor to this one– the Internet Exchange.

As we continue to expand our impact, we welcome new individuals who are passionate about these issues to join us. Your contributions can significantly bolster our mission. Please feel free to reach out and become a part of our journey!

In related news, the Open Technology Fund (for whom I am an Advisor) has announced its support of my work at the Center for Democracy and Technology, on this very topic.

AI-related publications of note:

- US pushing AI resolution in UNGA: https://www.axios.com/2023/12/13/us-ai-united-nations-global-resolution

- European Digital Rights asks “Is debiasing AI the solution?” https://edri.org/our-work/if-ai-is-the-problem-is-debiasing-the-solution/

- A member of the UN Secretary General's AI Advisory Body writes about the limitations of AI governance at this stage https://www.foreignaffairs.com/premature-quest-international-ai-cooperation

- A helpful taxonomy standard from NIST that defines adversarial AI https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/ai/NIST.AI.100-2e2023.pdf

And!

- Steve Song's 10th annual review of telecommunications infrastructure in Africa https://manypossibilities.net/2024/01/african-telecommunications-infrastructure-in-2023/

- Tech for Palestine launches https://techcrunch.com/2024/01/02/tech-for-palestine-launches-to-provide-tools-and-projects-to-help-advocate-for-palestinians/amp/?guccounter=2

- The Iranian government built an app to receive reports from everyday citizens if they spot a woman without a head scarf. https://filter.watch/en/2024/01/05/nazer-app-how-iran-is-using-technology-to-suppress-womens-rights/

Fragmentation or complexity? The literature on “internet fragmentation” extends more than a decade prior to describe everything from app localization to shutdowns. Its overuse is far too capacious, which has obfuscated real issues only some of which lead to harmful effects on users because of network isolation. We’ve lost the ability to say anything meaningful when we frame everything from consolidation in unregulated markets to overly regulated markets with the exact same term. One way to fragment the concept of fragmentation is by simply recognizing that the internet itself has become more and more complex, and how.

Thousands of standards bodies, regulatory regimes and deliberative spaces want to make changes to the internet as a means of progressing society, governance and commerce. The European Commission has a standards strategy that is fundamentally designed as an economic protectionist measure. The US has one, too. For people who still believe global internet standards implementation relies on the “free market,” while the rest of the global economy continues to evolve, then yeah, internet policy looks scary and like it’s ruining the internet. But the internet is way more complex than it was then, and the world in which it exists, is complex. These evolving complexities make the global standards bodies all the more important in this time of economic shift.

ICANN, IEEE, IETF, and the ITU should be embracing this complexity, or at least better preparing for it. There should, and will, be new players in standards bodies. There will be greater participation from states from the global south who have different and more interesting priorities than traditionally dominant standards participants. These new and different stakeholders will bring new and different areas of expertise and emerging technologies that, if standardised, would benefit more users in more places. All of this will lead to more complexity.

Moreover, governance institutions are proliferating. However any new initiatives need a clear mandate to be productive. Recent moves by the UN also purportedly stem from concerns over 'fragmentation' of the digital landscape, reflecting the view of states– particularly those in the global south– have on complex political realities of a changing digital world. Critics like me suggest that this approach might lead towards a centralized, hub-and-spoke model of internet governance, contrasting with the decentralized nature that has driven the internet's growth. This approach is detailed in a recent publication by the UN's Tech Envoy, highlighting the proposed structure and rationale for the Global Digital Compact. Rather, non-state stakeholders should lead on framing internet governance complexity as an embrace of plurality, because that is what has gotten the internet this far.

Finally, navigating at the intersection of policy and technical aspects in internet governance presents its own set of challenges. Introducing policy considerations into a domain traditionally driven by technical expertise and innovation can lead to tensions and complexities. Discussing social issues in technical terms results in technocratic solutions. Standards and industry fora are not ideal for resolving geopolitical conflict, though perhaps it is unavoidable. Broader socio-political considerations require expertise, too, which are often not in abundance in internet governance, though this is changing.

Through all of these competing considerations, it is still important to remain focussed on avoiding actual internet fragmentation. I find the “core of the internet” framework from the Global Commission on the Stability of Cyberspace instructive when thinking about internet fragmentation. Within this staggering complexity it identifies what the constituent pieces of the internet matter most. Those are:

- routing and packets (IP): the ability to direct data packets across networks using the Internet Protocol (IP), ensuring efficient and accurate delivery of information globally;

- naming and numbering (DNS): uniquely translates user-friendly domain names into IP addresses, allowing for the identification and location of devices and services on the internet;

- Encryption: encoding data to protect its confidentiality and integrity during transmission, ensuring user privacy, secure communication and safeguarding information from unauthorized access or tampering; and

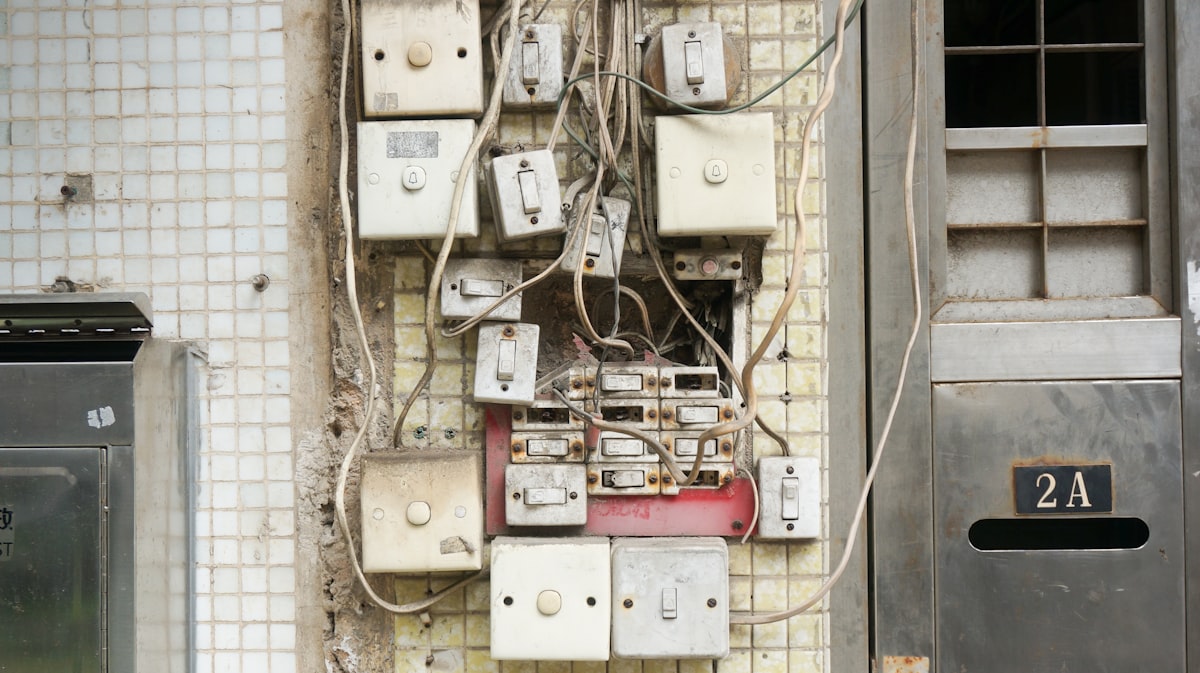

- physical communications infrastructure: the tangible elements such as cables, satellites, and data centers that are fundamental to the internet's operation, providing the essential backbone for global digital connectivity.

These elements must be protected and remain strong to avoid fragmentation, and no matter how complex the policy or technical landscape becomes, they must not be disrupted or even eroded in their operations. Going beyond minimum requirements, it’s important to note that this framework doesn’t address access issues, either to extend access or to ensure meaningful access by populations under heavy censorship. Circumvention technologies and infrastructure resilience, such as VPNs and proxies, can give users more control and agency over the way they connect and what, or to whom, they can connect.

“Fragmentation”, “complexity” or both: Sovereignty needs to be balanced against interdependence. Globalization– and its technologies– arose from the idea that interdependence prevents conflict. Economic interlinkage, or entanglement, disincentivizes attacks because it raises the risk of collateral damage and unintended consequences for the attacker. Perhaps some healthy fragmentation provides greater opportunity for interdependence beyond interconnectivity, and is an example of how to embrace a more complex internet landscape. No matter the phrasing, the fragmentation or complexity concept requires actors in internet governance to find ways to balance interests such that the internet is strengthened.

Comments ()