The Dog that Caught the Car: Britain's 'World-Leading' Internet

Billed as a “world-leading” child-protection law, the UK’s Online Safety Act has instead normalized surveillance and ID checks. “Tech policy wonk" Heather Burns writes that the model is spreading across the Atlantic, where politicians see a ready-made tool for censorship and control.

The UK’s Online Safety Act was sold as a “world-leading” child-protection law, one that would establish the UK tech sector as a global safety-tech powerhouse. Instead, it has normalized the idea that governments can bolt identity checks and surveillance layers onto the internet. Now that blueprint is crossing the Atlantic, where authoritarian-minded politicians see it as ready-made kit for censorship and control.

In the July 17 edition of Internet Exchange, Audrey Hingle laid out the risks to privacy, equality, and effectiveness raised by the age verification regime in the UK's Online Safety Act (OSA). Many civil society advocates warned the UK government and the Act's advocates that these risks would come to pass. We did so for more years than any of us care to remember, in ways that felt like deja vu at best, "Groundhog Day" at worst. In response, we were called big tech shills, tech libertarians, apologists for child exploitation, and enablers of the worst of humanity; some of us, including this author, were called far worse.

Safety for Sale

The problem was not that the people at the opposite end of the table did not understand the risks at hand, or, as is commonly assumed, the technology of the internet. The problem was that one of the the Act's main policy goals was to create a market, and a marketplace, for the British safety tech sector. That includes age verification providers. In the aftermath of Brexit, which drove away tech talent and investment, the UK desperately needed a digital success story. That success story, in the Conservative vision, would come through expanding the use of British technology for law and order. Hence lawmakers drafted the OSA to mandate the integration of an age verification wall, as a compliance requirement, for the over 100,000 service providers in scope of the law; and hence the revolving door between the online safety regulator, Ofcom, and the age verification software lobby. In this vision, the Great British Internet stack would simply have a few extra technical layers: innovations which would keep people safe whilst boosting British industry. Who could possibly have a problem with that? That's right–those pesky civil society technologists. By nagging politicians about fundamental rights and surveillance technology, we weren't just standing in the way of a law promoted as being about child safety; we were failing to "back Britain".

That Conservative vision for the Great British Internet was accompanied at all times with the catchphrase "world-leading". Freed from the clarity of the EU's Digital Single Market strategy, in which the UK went from being part of a trading bloc of half a billion people working under a common set of regulations to being an embittered island (plus a bit) making up its own rules for a market of seventy million, the UK set out to craft its own way forward, one which other nations would surely rush to emulate. Suffice to say that by the fifth year of clause-by-clause contention over the draft Bill, the civil society joke–take a drink every time the UK government refers to the OSA as "world-leading"–stopped being a joke and started to sound like a good idea.

In those days, I warned policymakers that their nationalist surveillance capitalism model might not inspire the "world-leading" reputation they wanted. One technically competent Labour MP, then in opposition, retorted:"we shouldn't legislate around what other countries might or might not do." So much for "world-leading." Here was a preview of how Labour would approach the OSA, its dubious Conservative inheritance, once in power: if the UK's "world-leading" model was copied for good, they would claim credit. If the UK's "world-leading" model was copied for bad, they would wash their hands of it. Laws built on magical thinking tend to create more of it.

What neither the Conservatives nor Labour counted on was the second Trump administration.

A World-Leading Model for Digital Racism

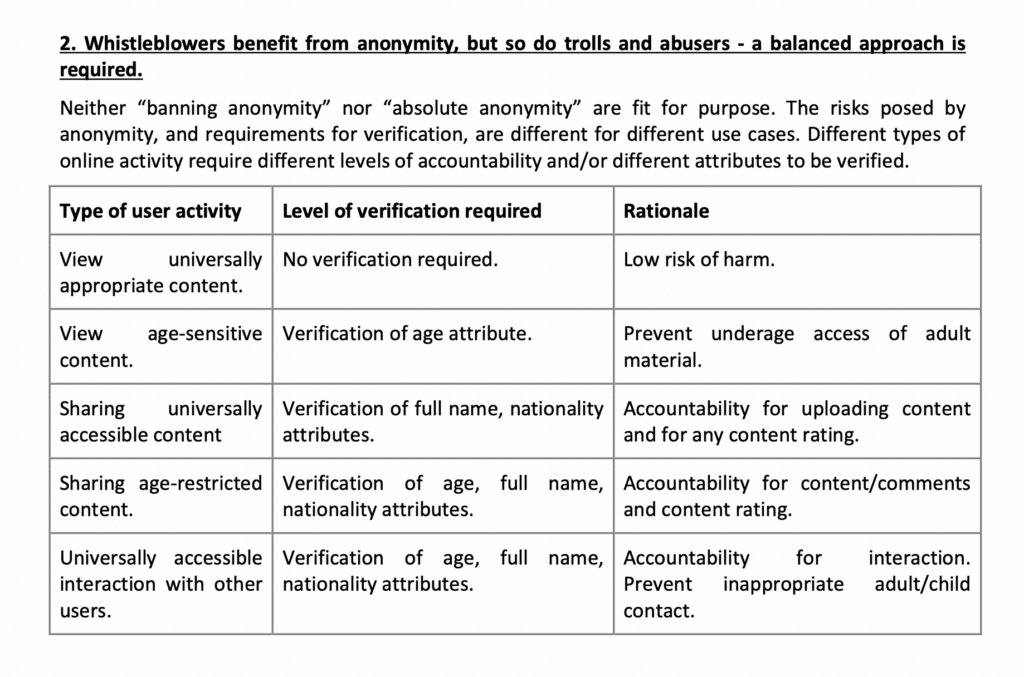

In September 2021, in my last miserable day of a miserable job, I wrote a blog post in my professional capacity about a meeting I had attended with a group of age verification software vendors. As I wrote, these lobbyists—well funded, well connected, and working at the heart of Parliament—were campaigning to have the then-Online Safety Bill's age verification measures expanded to require nationality checks. Imagine having to prove your nationality through a passport or national identity card as part of today's mandatory age verification checks, and you get a sense of how the lobbyists wanted the Great British Internet to work.

The meeting's attendees, all affluent white English elites, worked hard to build a rationale for why nationality checks as a condition for access to information and interaction made perfect sense. The naked opportunism on display as they glibly touted their wares as a means to identify, segregate, and suppress was unforgettable. The Online Safety Act provided policy experiences that no amount of training could prepare you for.

Four years on, that meeting was the first thing I thought of when I learned that a US appeals court judge had penned a legal rationale for why non-US citizens within the US are not entitled to First Amendment rights, meaning the US government could censor or surveil online speech by non-citizens. That dissent tested the waters to tell a certain political demographic within the US what they want to hear. And what they want to hear is that segregating and suppressing any given group of internet users based on identity, rather than on account registration, content, or adtech, is both technically possible and easily deployable. That is the "world-leading" promise of the Online Safety Act and the surveillance technology peddlers who love it. If this dystopia continues as it is, and that opinion is elevated from a dissent to a working policy, the technology needed to enable it is ready to go, made in Britain™.

That technology could also be deployed in the aftermath of Netchoice v Fitch, a failed lawsuit over Mississippi's child safety law, which raised the prospect of excluding children (regardless of citizenship) from First Amendment rights. Identifying children, not just for site access, but as a matter of who has constitutional rights, would require official documents. Documents which, conveniently, also note the child's nationality. As you may have noticed, children of the "wrong" nationality often find themselves excluded from America's already limited protections.

Mississippi's law, for what it's worth, was modeled on the Kids Online Safety Act (KOSA). KOSA, in turn, was inspired by the UK's Online Safety Act, with enthusiastic participation from this side of the pond. Put another way, Mississippi took the UK's "world-leading" model, filtered it through the worldviews of team Trump, and pushed it through so brutally that it has forced platform-level blocking and raised Constitutional issues.

None of this would have been possible without the Online Safety Act, which legitimized the notion of an age and identity layer within the internet stack and jingoistically encouraged the growth of the surveillance technology market designed to enable it. That market now stands ready to enable–and profit–from racist authoritarianism.

Karen Wants to Speak to Wikipedia's Manager

Then there is the case of Wikipedia, whose legal challenge to the Online Safety Act's categorization tiers was recently dismissed in the High Court on the technical grounds that Ofcom has not yet placed Wikipedia into the Category 1 tier, even though that is only a matter of waiting for the bureaucracy to catch up. As laid out by Ofcom, Wikipedia will fall into the highest tier of compliance, as if it were Facebook, requiring all global contributors of any age, not just British ones, to (amongst other things) have their ages verified to make sure they are neither precious British children, nor precious British children accessing 'harmful content'. Wikipedia was singled out as a target for top-tier compliance obligations as early as 2019, due to the fact that there are articles about suicide, self-harm, and eating disorders on it, which in Conservative minds meant that Wikipedia was willingly encouraging these things. Achieving this compliance requirement will require the insertion of an age verification layer which could easily be repurposed to identify individual contributors, many of whom depend on Wikipedia's anonymity to protect their personal safety.

A database full of Wikipedia contributors' identities would be manna from heaven to Republicans on the US House Oversight Committee, who have sent a Karen-esque letter to the Wikimedia Foundation demanding that they turn over the identities, IP addresses, and activity logs of Wikipedia contributors who have written encyclopaedia articles on Israel–Palestine. The Wikimedia Foundation's legal challenge in the UK courts has delayed the rollout of age checks for Wikipedia contributors, and thank goodness for that. If the age verification layer were already in place, the Committee would already have all of the data they need for the witch-hunt they crave. Thanks to the Online Safety Act, it is only a matter of time until they do.

Congratulations, Britain, You're World-Leading.

These legal and political salvos against privacy and freedom of expression, crafted in Britain and now crossing the Atlantic, have unfolded barely two months into the OSA's full compliance requirements. From here, the requirements will get stricter, the enforcement will get more aggressive, and the erosion of rights will accelerate. Next, Ofcom will mandate the rollout of proactive content detection technology, which introduces a general monitoring obligation on the Great British Internet, a move celebrated after Brexit freed the UK from the EU e-Commerce Directive, which had prohibited such obligations in domestic law. In the Brexit mentality, it is better to have a bad domestic law than a sensible European one. UK politicians will tout this model, too, as part of the UK's "world-leading" approach.

Whilst the proactive content detection regime currently covers only CSAM and terrorist content, that is because the aforementioned civil society troublemakers fought tooth and nail to limit it to just that. As originally written, the draft Bill included subjectively harmful but legal content within that scope and allowed the Secretary of State for Digital, a political appointee, to define any content to be brought within that scope for explicitly political reasons. You can rest assured that authoritarians were watching that debate closely, and have learned from it. They will be smarter about it when it is their turn. Among them are American policymakers who have taken a broad view on who counts as a "terrorist."

Here is the point: nationalist surveillance capitalism in the UK and beyond is happening in parallel to America's slide into digital authoritarianism. America is providing the political and legal scenarios. But it is the UK, its surveillance technology market developed to boost Brexit Britain, and the legal framework crafted around that market's rent-seeking, which has normalized the idea that stacking multiple interception layers onto the internet is simple, patriotic, and lucrative.

You would think that the UK would be celebrating its "world-leading" achievement. Instead, outside of the usual happy-clapping from the advocates who have built comfortable careers for themselves around the Act, the UK's reception seems strangely negative. Perhaps the fact that Americans are openly blaming the OSA, and not the Trump administration, for "the destruction of creative freedom online" has influenced that somewhat. Well, that and the views that the OSA "is a licence for censorship – and the rest of the world is following suit", it "risks making everyone less safe", it is "stripping away that potential for self-actualization" and "harming creative expression", it constitutes "a thinly veiled effort to normalize censorship in the U.K. and expand surveillance of British citizens and guests within their borders", it is "[feeding] young people sanitized, mainstream or government‑approved narratives", it is "a facial recognition sham" and "an abomination [...] making us less free, not more safe", it introduces "the new book-banning" and enables "Free Speech for the 0.1%", and is "treat[ing] government speech control as a feature, not a bug." Those too.

In response, Keir Starmer's now-former Secretary of State for Digital, a nice guy who is stuck selling the mouldy sandwich that Theresa May made, went on telly to declare that people who oppose the act are "on the side of paedophiles.". (Oi mate, some of us were being called that long before it was trendy.) With advocates like that, who needs the OSA's critics?

It would seem that the UK is the dog that caught the car. After years of touting its "world-leading" (drink!) internet regulation model that would "take back control from Europe" (drink!) to "clean up the internet" (drink!), "bring social media to heel" (drink!), "rein in the tech giants" (drink!), and make Britain the "safest place in the world to be online" (drink!) by "tackling online harms through technical innovation" (drink!), Brexit Britain has got everything it ever wanted.

And it has no idea what to do now.

Mallory at UN Digital Cooperation Day

IX’s Mallory Knodel will be participating at the UN Digital Cooperation Day on September 22 in New York during the UN General Assembly High-Level Week. She joins the 14:30–15:30 ET session, Shaping Responsible AI Use Through International Standards and Cooperation, organized with ISO and IEC.

Marking the first anniversary of the Global Digital Compact, the discussion will focus on implementation: how international standards and capacity building can enable trustworthy, interoperable AI. Speakers will elevate Global South priorities, share practical country approaches, and build momentum toward the International AI Standards Summit 2025 in Seoul.

Support the Internet Exchange

If you find our emails useful, consider becoming a paid subscriber! You'll get access to our members-only Signal community where we share ideas, discuss upcoming topics, and exchange links. Paid subscribers can also leave comments on posts and enjoy a warm, fuzzy feeling.

Not ready for a long-term commitment? You can always leave us a tip.

This Week's Links

Open Social Web

- A joint statement from members of the ActivityPub and AT Protocol communities urges collaboration instead of competition, rejecting the “winner-takes-all” framing and emphasizing that both protocols can coexist and strengthen the open social web together. https://hachyderm.io/@thisismissem/115157586644221109

- Signal is rolling out secure backups, an opt-in, end-to-end encrypted feature that lets users restore chats and media without compromising privacy. https://signal.org/blog/introducing-secure-backups

Internet Governance

- A new report from the Institute for Data, Democracy & Politics exposes how the booming social media monitoring industry relies on opaque access deals and data scraping, serving commercial interests while leaving public research needs unmet. https://iddp.gwu.edu/dashboard-data-acquisition

- Frederike Kaltheuner and Leevi Saari at AI Now Institute argue the “Brussels effect” is weakening in the face of US industrial policy and geopolitical pressure. https://euaipolicymonitor.substack.com/p/the-brussels-effect-meets-hard-power

- The Trump administration’s changes to the $42.5B BEAD program are sidelining rural fiber in favor of costly satellite subsidies, repeating past broadband policy failures, warns Christopher Mitchell, Director of the Community Broadband Networks Initiative and the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. https://communitynetworks.org/users/christopher

- The European Commission fined Google €2.95 billion for abusing its dominance in the Adtech market and ordered it to end these practices—potentially by selling parts of its business. Can the EU do what the US can’t? https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_25_2034

- Yevheniya Nosyk examines how Discovery of Designated Resolvers (DDR) is being deployed, revealing strong centralisation around just a handful of major DNS providers. https://labs.ripe.net/author/yevheniya-nosyk/discovering-the-discovery-of-designated-resolvers

- At AfriSIG 2025, Zambian cybercrime investigator Danny Mwinanu Mwala urged harmonised laws and multistakeholder collaboration to strengthen Africa’s data governance and digital security. https://afrisig.org/2025/06/04/afrisig-2025-advancing-data-governance-through-the-lens-of-cybercrime-investigation

- You can now download slides, photos, and other resources from the Global Digital Compact event on the Global Digital Collaboration site. https://globaldigitalcollaboration.org

- A new IRTF mailing list, ARMOR, brings together experts to tackle traffic tampering and shape research on resilient connectivity. Subscribe if you want focused, technical discussion on real-world countermeasures and a chance to influence an emerging IRTF research agenda on resilient connectivity. https://mailman3.irtf.org/mailman3/lists/armor@irtf.org

Digital Rights

- Amnesty International, together with InterSecLab, Paper Trail Media, and partners including Der Standard, Follow The Money, Globe and Mail, Justice For Myanmar, and the Tor Project, has released findings from a year-long investigation called the Great Firewall Export. Reports from multiple organizations examine how Geedge Networks exported China’s Great Firewall technology to authoritarian regimes and the global systems that make digital repression possible.

- From Amnesty International, how a range of private companies from around the world have provided, and in some cases continue to provide, surveillance and censorship technologies to Pakistan, despite Pakistan’s troubling record on the protection of rights online. https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/asa33/0206/2025/en

- The Silk Road of Surveillance report exposes the significant collaboration between the illegal Myanmar military junta and Geedge Networks in implementing a commercial version of China’s "Great Firewall", giving the junta unprecedented capabilities to track down, arrest, torture and kill civilians. https://www.justiceformyanmar.org/stories/silk-road-of-surveillance

- InterSecLab’s Internet Coup report reveals how leaked files show Geedge Networks is exporting China’s Great Firewall technologies to governments in Asia and Africa, fueling the rise of digital authoritarianism. https://interseclab.org/research/the-internet-coup

- Led by “Great Firewall” architect Fang Binxing, Geedge Networks is exporting China’s censorship technology abroad. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/world/article-leaked-files-show-a-chinese-company-is-exporting-the-great-firewalls

- Fang Binxing’s censorship technologies also have ties to some of Europe’s most well-known tech companies. https://www.ftm.eu/articles/how-china-is-exporting-its-censorship-technology

- A new IODA initiative will track bandwidth throttling, highlighting how governments increasingly use slowdowns as a subtle yet severe form of internet censorship that leaves connections technically online but functionally unusable. https://ioda.inetintel.cc.gatech.edu/reports/shining-a-light-on-the-slowdown-ioda-to-track-internet-bandwidth-throttling

- Nepal announced it will block access to major platforms including Facebook, X, YouTube, and Instagram after they failed to register locally as required by law, a move the government says targets online hate and cybercrime but digital rights advocates warn undermines fundamental freedoms. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2025/9/4/nepal-moves-to-block-facebook-x-youtube-and-others

- UNFPA has published a resource compendium on technology-facilitated gender-based violence. https://www.unfpa.org/resources/unfpa-resource-compendium-technology-facilitated-gender-based-violence

- Janet Haven, executive director at Data & Society Research Institute, shares testimony from former UN Special Rapporteur David Kaye on why the real threats to free expression in the US come from within, not from European tech regulation. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/janethaven_written-testimony-of-david-kaye-activity-7370536157794713600-kY8G/?rcm=ACoAACWJ_HIBp2ruf2wVpyUwySkAKakbPfg5KLw

- ARTICLE 19’s new report warns that market-first connectivity strategies deepen digital inequality and calls for a rights-based approach to reclaim the internet for all. https://www.article19.org/resources/the-missing-link

- The State Department is withholding new funding for programs that help Iranians bypass online censorship, threatening a policy that has bipartisan support and aligns with the Trump administration’s strategy of “maximum pressure” on Tehran. https://www.washingtonpost.com/national-security/2025/08/25/state-department-iran-censorship-internet

Technology for Society

- This study of 194 UK tech policy documents shows that while “stakeholder” is invoked to suggest broad inclusion, in practice the voices shaping policy remain narrow, with significant gaps between rhetoric and representation; using queer performativity theory, the analysis reveals how the term constructs roles, hierarchies, and exclusions in UK tech policy. https://policyreview.info/articles/analysis/stakeholders-uk-tech-policy

- In AI & SOCIETY, Samuel O. Carter and John G. Dale propose a framework of algorithmic political capitalism to tackle bias in algorithms by linking power, policy, and technology to democratic accountability. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00146-025-02540-2

- Cory Doctorow explains why Wikipedia works despite its chaotic reputation: instead of verifying facts, it verifies sources, requiring all assertions to be backed by reliable references. https://doctorow.medium.com/why-wikipedia-works-655edcfd9e57

- MediaJustice has released “The People Say No: Resisting Data Centers in the South", the first regional analysis of how Big Tech’s $100B+ data center boom is harming Southern communities economically and environmentally. See “upcoming events” below for a link to join their live launch. https://mediajustice.org/resource/the-people-say-no-report

- James Ball argues that focusing on individual ChatGPT queries misses the point, the real environmental question is how AI’s rapid infrastructure growth will shape global energy and water use. https://www.transformernews.ai/p/ai-energy-water-use-environment-argument-wrong

- Christianity is experiencing a resurgence in Silicon Valley, where faith groups like the Acts 17 Collective are drawing tech workers, entrepreneurs, and investors back to religion. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/gift/8b667ea9587e419a

- In Logistics and Power, Susan Zieger reveals how the hidden systems that move goods, people, and data shape modern capitalism—fueling consumerism, surveillance, and ecological crisis. https://bookshop.org/p/books/logistics-and-power-supply-chains-from-slavery-to-space-susan-zieger/e41e04d6cd6b3ed8?ean=9780520402874&next=t&next=t&affiliate=25948

- In The Consumption of Energy by Data Centres: Implications for the Global South, Lydia Powell and Akhilesh Sati warn that the rapid growth of AI-driven data centers risks deepening global inequality by raising energy costs, driving emissions, and leaving the Global South with little of the economic benefit. https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-consumption-of-energy-by-data-centres-implications-for-the-global-south

- Catherine Karimi Gichunge, part of M-Pesa’s original team, discusses how Africa's most iconic fintech was built through years of piloting, on-the-ground hustle, and financial innovation on the F-Squared Podcast. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tuKOuE8z2m8

Privacy and Security

- The Global Encryption Coalition warns that the Danish Presidency’s draft EU CSAM regulation would mandate ineffective client-side scanning, undermine end-to-end encryption, and threaten human rights and security. https://www.globalencryption.org/2025/09/gec-steering-committee-statement-on-1-july-text-of-the-european-csa-regulation

- 617 scientists from 35 countries also warn that the EU’s revamped CSAM plan still undermines end-to-end encryption and won’t work at scale, urging rights-preserving child protection instead. https://csa-scientist-open-letter.org/Sep2025

- Related: There’s no such thing as a safe backdoor. “Lawful access” means building a weakness into encryption that governments promise only they’ll use. History shows us that every lawful backdoor eventually becomes a criminal’s front door. https://jirif.substack.com/p/the-lawful-access-problem-every-backdoor?r=1mxk41&triedRedirect=true

- In a lawsuit filed Monday, the former head of security Attaullah Baig for WhatsApp accused the social media company of putting billions of users at risk. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/09/08/technology/whatsapp-whistleblower-lawsuit.html

- Justin Hendrix breaks down Baig’s claims of systemic security failures, retaliation, and even falsified reports that left WhatsApp vulnerable to mass data access and daily account compromises. https://www.techpolicy.press/breaking-down-the-whatsapp-whistleblower-lawsuit/

- Paradoxes of Authoritarian Mundane Surveillance shows how Russia’s use of everyday digital services for mass monitoring backfired when a Yandex.Eda data leak enabled journalists to trace the powerful through their own routines. https://ojs.library.queensu.ca/index.php/surveillance-and-society/article/view/18391

- On the Terms of Service podcast with Clare Duffy, Riana Pfefferkorn, policy fellow at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence, explains how DMs and texts aren’t always private, and shares tips to better protect your conversations. https://edition.cnn.com/audio/podcasts/terms-of-service-with-clare-duffy/episodes/563b9a5c-25e7-11f0-a31f-cb00ed6a8850

- The US and allies warn that critical open-source dependencies are a national security risk. Protect yourself by locking your mobile account and using biometric passkeys instead of SMS for two-factor authentication. https://opencollective.com/opensource/updates/public-service-announcement-re-salt-typhoon

Upcoming Events

- The People Say No: Resisting Data Centers in the South. September 17, 4:30pm ET. Online. https://mediajustice.zoom.us/webinar/register/WN_X631jbaHQzWOPYBhuW8V0w#/registration

Careers and Funding Opportunities

- OpenAI has launched the People-First AI Fund, a $50 million initiative to support US-based nonprofits using AI for public good. US. https://openai.com/index/people-first-ai-fund

- Center for Information Technology Policy: CITP Technology Fellows Program. Remote and Princeton, NJ. https://citp.princeton.edu/programs/citp-technology-fellows-program

- TUC: Policy & Campaigns Officer, Technology and Artificial Intelligence. London, UK. https://tuc.current-vacancies.com/Jobs/Advert/3942211?cid=1996

- Institute for Law and AI: Seasonal Research Fellowships. Multiple Locations. https://law-ai.org/seasonal-research-fellowships

Opportunities to Get Involved

- You have one more week to submit your proposal for RightsCon 2026 (May 5-8, Zambia and online). The deadline has been extended to September 19. https://www.rightscon.org/your-guide-to-a-successful-proposal

- BASIS: AI Policy Fellowship will mentor a small, dedicated cohort of students eager to learn more about AI policy. Applications are due by end-of-day September 20. https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSf5zbuR-Z4aFGQofP-9lhCexdZ7X4sQemZ4TiPt8eTJYaePUw/viewform

What did we miss? Please send us a reply or write to editor@exchangepoint.tech.

Comments ()