WHODIS? WHOIS.

Identity on the internet: Digital identity has become a central priority for service providers, governments and users of the internet. From authentication to credentials to passwords and, of course, user privacy considerations, the ideas space is pretty crowded. At the same time, cooperation in standards and across standards development organizations remains challenging.

The Internet Architecture Board posed a programme that would bring experts together, calling it Wholistic Human-Oriented Discussions on Identity Systems (WHODIS). The community ultimately rejected the idea. This might indicate the need to take a step back and articulate a more principled approach to identity design online:

- verifiable identity online should be rare.

- users need fit-for-purpose options and no one solution can provide that.

- identity is granular and that is a built-in privacy feature.

- incorporate real-world trust features.

- leverage existing trust/transaction relationships users already have.

What else? Email back with your thoughts.

Verified gossip:

- The ITU-R sector conference, WRC-23, will be issuing its report tomorrow. Look out for a published letter signed by 43 countries in support of Ukraine and condemning the illegal seizure of its radio frequency resources by Russia. The Ukrainian delegation read the statement during the main session of the conference.

- At the end of October RIPE NCC published a new policy document on Voluntary Transfer Lock, motivated by Ukrainian internet operators who were losing their IP and ASN space to Russia.

- Check out this delightful long read on the relationship between interoperability and innovation as told through the case of podcasting: https://cdt.org/insights/understanding-innovation-in-interoperable-systems-a-podcasting-case-study

- E2EE in Messenger and Instagram– big news! But not so fast, until server-side encrypted backups for all messages and their attachments are optional by default, I have concerns.

- Nick Doty explains the easy-to-use Global Privacy Control (GPC) as a universal opt-out mechanism to help consumers communicate their data privacy preferences automatically to websites. The standardization of GPC is vital for user privacy across different browsers and websites.

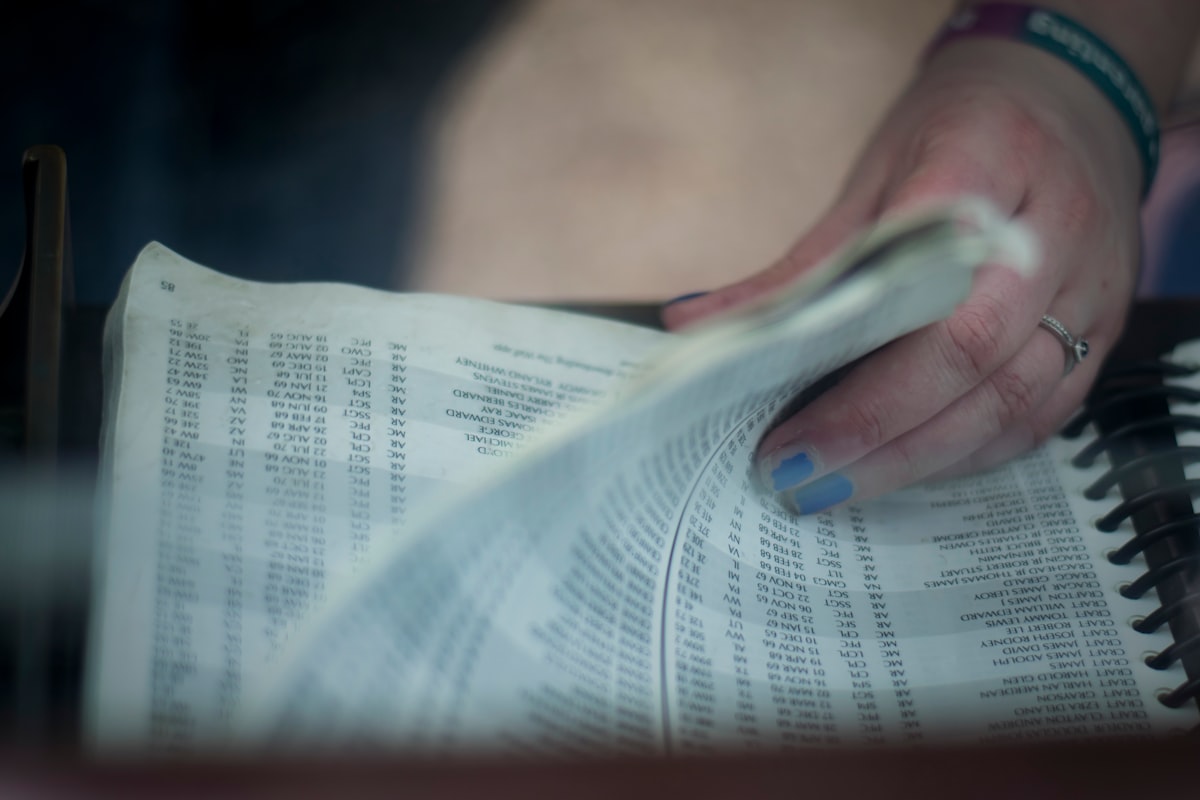

An epitaph for WHOIS: Whois is a public directory of contact information for domain registrants. It exists no more. It has been a long time coming, this epitaph for Whois, because it is only now after five years that we finally have some clarity about what is being done with domain registrant data, what there is to learn in the governance of finite internet resources, and whether we can ever truly recover from this singularly nightmarish use of private data.

We say that groups and individuals can “own” domain names like exchangepoint.tech, but in fact your payment to a registrar is only for the use of a domain name and enters you into a contractual relationship with that registrar, the registry that maintains the top-level (.tech), and ultimately with ICANN, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers. Under the terms of domain contractual agreements, purchasers must be registered and their contact details shared with ICANN.

Now it seems a bizarre idea to publish the names, personal addresses and phone numbers of anyone who has ever paid to use a domain. We remember our internet history: an entire industry sprang up around domain names, now known as the dot com bubble, and it’s one of the reasons we need ICANN in the first place: to make sure the finite resource of domain space is properly governed. One aspect of the industry was created around Whois being a privacy nightmare, and that is privacy protection, in which you can pay $9.99 for the registrar or registry, or some third party, to put its contact details on your domain instead of your own.

But the beginning of the end for Whois occurred even before domain privacy hucksters and data protection became mainstream. Back in 1995 the EU first introduced a strict regulation on data protection. Yet ICANN did nothing about Whois. And then the internet world all knows what happened in 2018: GDPR, which effectively took decades old data privacy legislation and made misuse of private data a finable offense. Considering the volume of contact details in Whois, ICANN and domain sellers were looking at significant costs in fines annually if they didn’t take down Whois. In fact in 2019 the first decision applying GDPR was to ICANN’s Whois.

So on 25 May 2018 Whois was over. Though mirrored copies of it still live online today, and many registrars still maintain queryable databases for internet resources, ICANN lifted the requirement to offer a Whois service, issued a temporary specification for registrant data to its contracted parties, and initiated an “emergency” policy development process to deal with designing its replacement.

(Spoiler: Its replacement was delivered two weeks ago. November 2023. Please take a moment to appreciate the article titled, “The pricey, complex, clusterfuck plan to reopen Whois”.)

Public interest advocates who have been vocal against the Whois. Privacy. Nightmare. for years are left asking, “Why does Whois even need replacing?” It turns out there are good reasons to want to know the owner of a domain given the amount of dangerous and illegal content on the internet (criminals purchasing domains for ransomware and enjoying privacy protection for an additional $9.99 notwithstanding). Nonetheless, hitting the right balance in ICANN policy between accountability and privacy is important, as it is in other internet governance fora.

ICANN’s policy processes led to guidance one year later in May 2019, though this guidance was slow to implement and registries and registrars increasingly focused on compliance with local and regional jurisdictional law. And just a few days ago ICANN launched a service to facilitate look up requests that meet certain requirements, but unlike Whois it’s a service that ICANN doesn’t really provide: the Registration Data Request Service (RDRS) simply connects requestors with registrars.

This is not the end.

It’s important to remember that while Whois is a privacy nightmare for registrants, legitimate access to registrant information needs to be swift and quick. ICANN policy development had to strike a balance between privacy and access in the case of Whois the balance is always critical, and this is left to the ICANN community, not ICANN itself who cannot be the gatekeeper, to determine the mechanisms by which security researchers or abuse mitigation can obtain privileged access to registrant data.

As an aside, there exists another example in which ICANN has recently taken this approach. ICANN is a key actor in internet health and cybersecurity, albeit indirectly through its role in internet governance. It has set new obligations for contracted parties to mitigate DNS abuse, which significantly shifts the cybersecurity landscape but without itself taking actions against abuse. And while registrars have always said that they work on disinformation and cybersecurity threats to take down domains that are abusive, free speech advocates need to watch the DNS abuse mitigations practices evolve to ensure interests remain balanced.

RDRS will not always work and law enforcement has long decried Whois “going dark”. However, requiring a warrant or subpoena for access to personal data of registrants isn't that radical. There are already a number of registries, including the country-code registries, which are not subject to ICANN’s rules, that already operate in this way. Everyone who is involved in Whois research — be they criminals using domains for fraud, Whois scraping spammers, or anti-abuse researchers — is already well aware of limitations to this data given domain privacy services. It's far better that there is universal clarity on baseline privacy protections, on top of which can be built mechanisms of investigation as well as jurisdiction-specific regulation.

Some predict that law enforcement agencies will continue to seek blanket access, effectively warrantless search, either through policy iterations or technical integrations. Some registrars may already be keen to provide this frictionless access for certain entities. It’s critical that civil society watchdogs of surveillance powers pay attention to the evolution of RDRS.

Beyond watching DNS abuse and access to registrant data, what can multistakeholder participants in ICANN learn from the tortured Whois example? What can we all learn?

I start back in the 1990s, mid-bubble, when privacy advocates had clearly expressed concerns with Whois, pointing to the EU directive (yet to be regulation) that contracted parties submit names, addresses and other details to a wide open database that anyone could query. ICANN had a simple solution: drop the requirement for Whois and leave it to businesses to comply with their local laws.

Whois may reflect the messy legislative landscape on privacy. Even so, it should not have taken so long to agree on what is essentially a universal privacy policy for domain registration that leaves discretion of disclosure to data controllers. Law enforcement and intellectual property interests were allowed to derail discussions, at times even leveraging civil society groups that align with “open internet” principles.

Like privacy, other digital issues will inevitably complicate messy and patchwork legislative landscapes in the future. Global internet governance bodies like ICANN should help to harmonize the policy landscape by grounding internet standards and policy making in a strong commitment to human rights. Companies developing the interoperable internet technology can more easily fulfill their responsibility to human rights. And states, the stakeholder group with actual obligations to human rights, can better align their laws with ICANN’s global policy.

Comments ()