Democracy Needs Encryption

Encryption protects fundamental rights, and it must be preserved as governments expand their cybersecurity and investigatory powers.

By Mallory Knodel

At IGF 2025, I had the privilege of speaking at the Parliamentary Session “Striking the Balance: Upholding Freedom of Expression in the Fight Against Cybercrime” as a representative of the Global Encryption Coalition. Below is a summary of my remarks, which focused on how encryption protects fundamental rights and why it must be preserved as governments inevitably seek to expand their cybersecurity and investigatory powers. Stay tuned to civil society advocacy positions in anticipation of the upcoming Signing Ceremony of the United Nations Convention on Cybercrime in Hanoi, an event that marks a global shift in how governments approach cybersecurity and human rights for years to come.

The Global Encryption Coalition was founded in 2020, following a pre-meeting at the Berlin IGF in 2019. We launched in response to increasing legislative attacks on end-to-end encryption, especially in a few key jurisdictions, notably the Five Eyes countries. The goal was to bring together private sector voices, civil society, scientists, computer scientists, and cryptographers to align and speak out about the benefits of encryption and the importance of protecting it.

I joined through my role as Chief Technologist at the Center for Democracy and Technology, one of the founding secretariat members. Today, I serve as one of the coalition’s technical specialists. Our membership is primarily civil society organizations, small and medium-sized enterprises (not large tech firms) and academics from around the world.

In addition, I’m active in the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and the Internet Research Task Force (IRTF), where I chair the Human Rights Protocol Considerations research group. Some of these issues overlap with freedom of expression, although the group’s mandate is broader. Still, I’m glad to bring that perspective into this discussion.

On the subject of cybercrime: when I was at CDT, we participated as observer members in the UN’s Ad Hoc Committee [on the UN Cybercrime Treaty]. I followed that process closely, and I carry many thoughts from it—especially from the civil society perspective.

Encryption protects all human rights, not just privacy. As the UN has long recognized, it also supports freedom of expression, opinion, and association. To avoid being overly broad, let me get specific.

In more than 15 years of work in civil society and the nonprofit world, I’ve seen that we can be strident in our advocacy. But that’s because we’re part of a much longer historical struggle, one that predates the digital age. Democracies have always wrestled with striking the balance between investigatory powers and human rights. The difference today is that we now have technical mechanisms that can help enforce those limits. Encryption is perhaps the most powerful example: it lets individuals say, “This conversation is private, and I decide who can access it.” That’s a profoundly democratic capability.

From the civil society perspective, the goal is to restore a better balance of power between people and institutions. Unfortunately, recent years have tipped that balance toward law enforcement and investigatory agencies. There’s a tendency to overcorrect, and we keep learning the hard way that weakening security technologies like encryption creates vulnerabilities; vulnerabilities that can and will be exploited.

One common narrative is that technology moves faster than policy, and laws need to “catch up.” Too often, that narrative is used to argue against the widespread, democratic use of technology, suggesting people are the threat and must be reined in. But we don’t hear the same urgency when governments use technology in unaccountable or extralegal ways.

Mass surveillance, or even targeted surveillance without proper oversight, is a clear example of technology outpacing policy. From a civil society perspective, this imbalance is obvious, yet it is often overlooked in debates about cybercrime.

There’s also the matter of scale. In the pre-digital world, there were natural limits to what could be known about an individual. With the digitization of our lives, those limits are gone. Companies collect, generate, store, and analyze enormous amounts of data. Governments almost inevitably want access too. But this exceeds what our societies were built to handle in terms of boundaries between public and private.

Encryption is the only tool we have that can reintroduce some of those boundaries. And it’s not just a shield from governments, it’s also a shield from companies. Many users, especially human rights defenders and journalists, rely on encryption to protect themselves from corporate surveillance as well.

From that perspective, here are a few jurisdictional recommendations:

- Protect cybersecurity research. Civil society, academics, and private-sector researchers must be free to probe and audit systems. Don’t criminalize those efforts, they make us all safer.

- Strengthen limits on surveillance. If states are expanding their cybersecurity capabilities through international cooperation, domestic safeguards must be strengthened, not weakened.

- Ensure responsible and transparent investigatory powers. Any cooperation between governments and companies should be independently overseen. Government hacking, backdoors, and zero-day exploits pose enormous risks to cybersecurity.

- Improve standards in international agreements. Many civil society groups believe the UN Cybercrime Treaty lacks sufficient human rights safeguards. But there’s nothing stopping jurisdictions from exceeding those minimums. Governments can and should do more to protect journalists, activists, and human rights defenders.

I closed with a question: I think the core dilemma in all of this is whether we’re designing policy and technology to protect people or to protect against them. Are we leaning into democracy, or are we afraid of it?

If we start by putting people at the center of security, privacy, and rights, the tensions begin to soften. That’s the direction we should be aiming for. It will take political will, and maybe the political moment isn’t quite here yet. But we can imagine it, and that vision is worth holding onto.

Help Shape the Future of the Fediverse: Take the Needs Assessment Survey

Are you an admin, moderator, or community organizer in the Fediverse?

The annual Fediverse Needs Assessment survey is open and your input matters. It collects data on safety challenges, moderation gaps, operating costs, revenue, and team size to help shape tools, policy guidance, and advocacy that reflect real community needs. Last year moderators representing more than 4.3 million accounts took part. This year response rates are low and we need your voice. The survey is quick, anonymous, and makes a real impact.

Support the Internet Exchange

If you find our emails useful, consider becoming a paid subscriber! You'll get access to our members-only Signal community where we share ideas, discuss upcoming topics, and exchange links. Paid subscribers also get a free sticker, can leave comments on posts, and enjoy a warm, fuzzy feeling.

Not ready for a long-term commitment? You can always leave us a tip.

This Week's Links

Open Social Web

- Bounce Beta is live and ready for users to try out! This first-of-its-kind service enables users to migrate their follow graphs between ActivityPub and ATProto with Bridgy Fed as a mediator. https://blog.anew.social/bounce-beta-now-live

- A new study in Integrative and Comparative Biology finds that while Twitter once dominated among science communicators, most have now left, with Bluesky emerging as the top alternative. https://www.wired.com/story/bluesky-now-platform-of-choice-for-science-community

Internet Governance

- The co-facilitators of the WSIS+20 review have released the Zero Draft, an initial version for negotiation and comment, outlining priorities on digital divides, human rights, sustainable development, and internet governance. https://dig.watch/updates/zero-draft-of-wsis20-outcome-document-made-available

- The Canadian Internet Registration Authority (CIRA), which manages the .ca domain, has released a report urging renewal of the multistakeholder model as governments debate the future of internet governance in the WSIS+20 review. https://circleid.com/posts/technical-community-calls-for-stronger-smarter-internet-governance-in-new-global

- At the World Telecommunication Standardization Assembly 2024 (WTSA-24), the Internet Society worked to prevent the ITU-T from expanding its mandate in ways that could threaten the open, multistakeholder model of internet governance. https://www.internetsociety.org/issues/internet-governance/news-updates/netmundial10-9

- The Number Resource Organization’s RPKI Program is working to make the internet’s security system for routing (The Resource Public Key Infrastructure or RPKI) more consistent and trustworthy. https://www.arin.net/blog/2025/08/26/nro-rpki-program-series-5

- Geoff Huston reviews efforts to create a new governance model for the DNS Root Server System, noting that current proposals largely preserve the status quo rather than addressing long-standing gaps in accountability, funding, and operator selection. https://www.potaroo.net/ispcol/2025-08/rssgwg.html

- Australia said Tuesday it will oblige tech giants to prevent online tools being used to create AI-generated nude images or stalk people without detection. https://www.yahoo.com/news/articles/australia-tackle-deepfake-nudes-online-060821562.html

- XSLT is a declarative language for transforming XML into formats like HTML or PDFs. Though powerful, it’s poorly and sometimes insecurely implemented in browsers. Now, browser makers are debating whether to drop it for security and resource reasons, forcing sites that use it to rebuild, or update it at the expense of newer features. Mary Branscombe breaks down the debate in The New Stack. https://thenewstack.io/xslt-debate-leads-to-bigger-questions-of-web-governance

- SIDN has upgraded its RDAP service to the latest “profile 2024” standard and implemented ICANN’s Registration Data Policy, making it one of the first registries to pass all compliance tests. https://www.sidn.nl/en/news-and-blogs/sidns-rdap-service-upgraded-to-the-latest-specification

- New “scan your face” age-verification laws in the UK and US are backfiring: compliant sites that require government IDs or webcam scans are losing traffic, while major porn sites ignoring the rules are seeing record surges. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/08/31/age-verification-uk-porn-sites

- Chapter 1 of Remedies for Tech-Related Harms looks at bans, showing how regulators use tools like outlawing harmful technologies, removing executives, and requiring data deletion or retention limits. https://www.law.georgetown.edu/tech-institute/insights/remedies-for-tech-related-harms-chapter-1

- Republicans on the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee opened a probe into alleged organized efforts to inject bias into Wikipedia entries and the organization’s responses. https://thehill.com/homenews/house/5473331-wikipedia-bias-probe-republicans

- Brazilian stakeholders’ proposals on the AI regulatory sandbox are examined in Mapping the Future of AI Regulation in Latin America by Kenzo Soares Seto. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-86540-4_5

- Global telecom body 3GPP is racing to finalize Release 19 while laying the groundwork for 6G in its upcoming Release 20, holding meetings in Sweden and India. https://www.3gpp.org/news-events/3gpp-news/augwg-report

- India hosts first-ever meeting on 6G standardisation. https://www.thehansindia.com/karnataka/india-hosts-first-ever-meeting-on-6g-standardisation-1000910

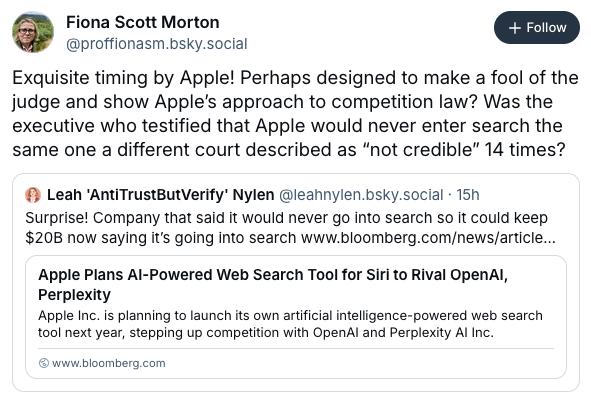

- A federal judge refused to break up Google despite ruling that Google illegally monopolized the online search and search-ad markets. https://www.politico.com/news/2025/09/02/google-dodges-a-2-5t-breakup-00540419

Digital Rights

- A new 7amleh report finds Meta let incitement and hate speech written in Hebrew spread unchecked while silencing Palestinian voices. https://7amleh.org/post/meta-s-role-during-genocide-en

- US authorities are using AI-powered surveillance tech made by Palantir and Babel Street to deliberately target non-US citizens and pose risks to those who speak out for Palestinian rights, said Amnesty International. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2025/08/usa-global-tech-made-by-palantir-and-babel-street-pose-surveillance-threats-to-pro-palestine-student-protestors-migrants

- In Turkmenistan, the same officials blocking the internet are secretly selling access back at exorbitant prices, turning censorship into a state-run racket. https://blog.torproject.org/Corruption-Control-Turkmenistan-internet-censorship-business

- A Baffler investigation finds that a law designed to dismantle the mafia is now being used by jilted fans to take OnlyFans and its management agencies to court. https://thebaffler.com/outbursts/tit-for-tat-french

- Digital human rights organization Bits of Freedom has initiated summary proceedings against Meta. The organization demands that Meta offer users of its apps Instagram and Facebook the option to choose a feed that is not based on profiling. https://www.bitsoffreedom.nl/2025/09/04/bits-of-freedom-initiates-summary-proceedings-against-meta-in-run-up-to-national-elections

Technology for Society

- New research shows that machine learning models can give conflicting results from small changes in training, and proposes new evaluation tools and selection methods to help identify models that are both fairer and more reliable; the authors also built and released a Python library that measures these instabilities alongside standard metrics, giving practitioners a richer toolkit for model selection. https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.04525

- As AI adoption grows, reliable and resilient Internet access will be critical for countries hoping to benefit economically and socially from the technology, writes Abhishek Vajjala for Internet Society. https://pulse.internetsociety.org/blog/why-ai-requires-a-resilient-internet

- The Digital Sovereignty Index offers a cross-border snapshot of self-hosted infrastructure, showing which tools countries actually use rather than their policies or intentions. https://dsi.nextcloud.com

- The Pulitzer Center’s AI Spotlight Series is a free global training program for journalists and editors to improve coverage of artificial intelligence. https://pulitzercenter.org/focus-areas/information-and-artificial-intelligence/ai-spotlight-series

- Switzerland just launched Apertus, which they describe as the world’s most powerful open-source multilingual AI model from a public institution, built on transparency, diversity, and public good. https://publicai.co/apertus

- The abrupt US funding cuts to global media and internet freedom have left journalists and civil society dangerously exposed. Andrew Ford Lyons, Director of the Global Technology Hub warns it’s a wake-up call to build more resilient support systems. https://internews.org/blog/the-global-impact-of-u-s-funding-cuts-on-journalism-and-internet-freedom

- Thirty years after its debut, the “Californian Ideology” still shapes Silicon Valley’s blend of counterculture and authoritarian capitalism. Nathan Schneider reflects on its resurgence in the age of AI and Trump. https://www.techpolicy.press/thirty-years-on-the-californian-ideology-is-alive-and-well

- US fighter pilots took orders from AI for the first time in a test that promises split-second combat decisions, but also raises questions about how much military judgment we’re ready to outsource to machines. (Personally, I’d say none.) https://www.semafor.com/article/08/27/2025/us-fighter-pilots-test-taking-directions-from-ai-for-the-first-time

Privacy and Security

- A policy brief from Chayn discusses why encryption is a feminist issue. https://chayn.medium.com/encryption-as-a-feminist-issue-a-policy-brief-e6a9366b77ad

- The FBI and global partners warned that a Chinese hacking campaign has now hit at least 200 US organizations and 80 countries across multiple industries. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2025/08/27/fbi-advisory-china-hacking-expansion

- Every day, private information is extracted from your devices. To prove it, Proton tracked YouTuber Tony Angelo for 24 hours to map all the ways he’s unintentionally leaking his information out to the world. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9wknq-Ra-KU

- The core of the Internet is notoriously vulnerable to attacks, with BGP and DNS being particular weak points. So Brucie Davie set out to learn about what has been done to secure these components of the Internet’s "core infrastructure.” https://www.theregister.com/2025/08/27/systems_approach_securing_internet_infrastructure

- As AI assistants gain the ability to control browsers, experts warn that malicious sites could embed hidden commands that hijack these agents, raising new security concerns with tools like Anthropic’s auto-clicking Chrome extension. https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2025/08/new-ai-browser-agents-create-risks-if-sites-hijack-them-with-hidden-instructions

Upcoming Events

- A livestream to promote Laura Bates’ new book The New Age of Sexism explores how AI amplifies threats to women, girls, and marginalized communities. Experts in digital rights, AI, and gender will discuss solutions and legal reforms for a more equitable digital future. September 9, 12pm ET. Online. https://equalitynow.org/event/the-new-age-of-sexism-ai-gender-and-the-urgency-of-legal-reform

- Women and Girls' Online Safety Conference 2025 aims to bring together researchers, practitioners, and policymakers from across all sectors to explore and address the pressing challenges to women’s safety in digital spaces. September 10-11. Milton Keynes, UK. https://university.open.ac.uk/centres/protecting-women-online/events/women-and-girls-online-safety-conference-2025

- Refuge UK tech Safety Summit 2025, a virtual event dedicated to tackling technology-facilitated abuse and economic abuse. September 23-24. Online. https://refugetechsafetysummit.vfairs.com

- CDT’s Tech Prom fundraiser is an opportunity for deeper connections, richer conversations, and a truly memorable experience. October 23, 6pm ET. Washington, DC. https://cdt.org/event/2025-tech-prom

- CyberChess is a cornerstone cybersecurity event in the Baltic region, bringing together a diverse community of experts - including cybersecurity specialists, policymakers, internet and telecommunications providers, industry leaders, and enthusiasts. October 27-30. Riga, Latvia and Online. https://www.icann.org/fr/engagement-calendar/details/cyberchess-2025-10-29

Careers and Funding Opportunities

- Gates Foundation: Senior Program Officer, Public Goods, Digital Public Infrastructure. Seattle, WA. https://gatesfoundation.wd1.myworkdayjobs.com/Gates/job/Seattle-WA/Senior-Program-Officer--Public-Goods--Digital-Public-Infrastructure_B021148-1

- Future of Privacy Forum: VP of US Policy. Washington, DC. https://fpf.org/vice-president-of-u-s-policy

- 2026 Tech Policy Press Fellowship Program. Remote. https://www.techpolicy.press/call-for-applications-2026-tech-policy-press-fellowship-program

What did we miss? Please send us a reply or write to editor@exchangepoint.tech.

Fediverse Finds

Posts worth boosting.

Comments ()